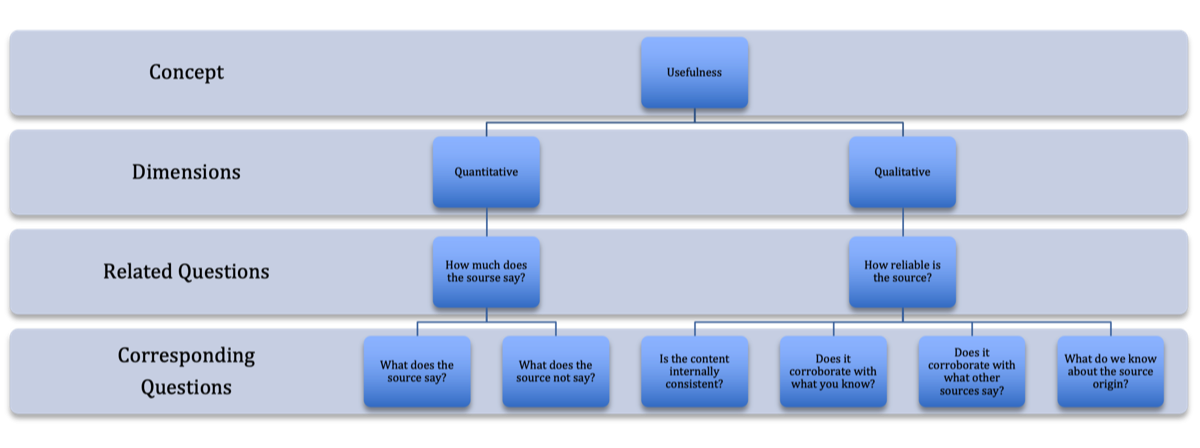

Another word for utility is usefulness. I won’t make a distinction between these two words here, and will use them interchangeably. Questions that ask you about how useful a source is require you to consider how the content of the source helps you to understand an issue, and the extent to which you can trust it to provide you with some understanding of the issue.

To answer this type of question, you need to consider 2 aspects:

- Quantity of the source – is the content of the source enough to help you understand the issue?

- Quality of the source – is the source reliable enough for you to find the source useful?

In this section, you will learn to examine a source’s utility (both quantitative and qualitative dimensions), so that you can determine the degree to which the source can help you to understand a certain issue. Before we do, let’s take a look at the diagram below:

Quantitative Dimension

How useful a source is can depend on HOW MUCH a source can tell us about an event or an issue. It’s basically the amount of information it carries that gives us an insight into an event or an issue. In a way, we can argue that the more a source can tell us about something, the more useful it is. The reverse is almost true. Let’s take a look at Example 1:

Source A

An account from a Chinese elderly man on his life in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation.

We were informed by our neighbour that when we pass by a Japanese sentry post, we must never forget to bow to the Japanese sentry, otherwise you may get a beating or be detained. When I passed by there, I was a bit nervous. I bowed and was allowed to continue my journey to my school. The Japanese came in [the school]and beheaded eight people and their heads were put into iron cages and hung up at eight different places and notices were put out beside the heads that ‘These eight people were beheaded because they did not follow the law of the Imperial Japanese Army’. The notice spelled out that if anyone caught in the act would be given the same treatment.

Whilst Source A is able tell us about the WHAT (what happened to people in Singapore during the Occupation); it’s not able to tell us the WHY (reason for Japanese Occupation). In other words, Source A is useful in its content only to the extent of telling us what happened to Singapore in WW2; but not why it happened.

Now, I hope you can understand that both the WHAT and WHY belong to the quantitative dimension of a source. What about the qualitative dimension of a source then?

Qualitative Dimension

Using Example 2 shown below, I’ll discuss the ‘qualitative’ dimension of a source and how it affects the usefulness of the source.

Generally, a credible source is also a useful source because we can trust the information enough to make use of it for our own understanding of a specific issue. The reverse is often true. However, these are not the only relationships between reliability and utility. There are two more relationships between these two concepts.

Below is a summary of the 4 possible relationships between reliability and utility:

Reliability

Utility

Remarks

✓

✓

- Common Occurrence

X

X

- Common Occurrence

✓

X

- When relevance is an issue

X

✓

- May occur when establishing the reliability of the source is not the key focus. For example, a propaganda material may not be trusted for its message but can still be useful to historians trying to understand how people in the society have been influenced by these materials.

How useful is the wife’s statement as evidence about the man who has been charged for a crime? Explain your answer.

Statement from the wife of a man charged for a crime, during a television interview.

He is a responsible man who makes rational and well-intended decisions. Although sometimes quick-tempered, he is seen by many as a man with integrity and compassion. I feel he has no part in the crime at all, he has always been a loving and faithful husband.

In this example, the wife’s statement is deemed reliable in telling us her husband has being a committed and supportive partner because she knows him well enough. So, if we were to ask about whether her statement would be useful in helping us know more about the man, we should most likely find the source useful in broadening our understanding of his character. The wife’s statement would have also satisfied the quantitative aspect of the question because we know enough from her statement to understand what kind of a man her husband is like. This is a classic case of a reliable source (understanding the man’s character) being a useful one as well.

However, there are also instances when a reliable source may not be useful. Refer to Table B.

✓

X

- When relevance is an issue

In this case, the wife’s statement about her husband’s character does not lend support to his innocence (a different topic). Even if we were to assume that her opinion about her husband’s character could be trusted, it does not mean it can be a piece of evidence to prove that her husband did not commit a crime. In other words, her opinion about his character does not have a direct bearing on the case. What is more crucial is to ask if the wife can provide a strong and unbiased alibi to prove her husband’s innocence. Did she witness the crime being committed by someone else? Does she have evidence to show that her husband is indeed innocent? Therefore, the wife’s statement is useless as evidence of her husband’s innocence because the credibility of her statement goes only as far as her husband’s usual character/personality is concerned, but not to the extent that she could show her husband was not the one who committed the crime.

To answer any utility question effectively, one must identify the topic of the question correctly, and understand whether the source’s reliability (if any) is relevant to the topic asked.

Credit: Example 2 contributed by Michelle Soon